4

Findings

Before discussing the results of the practical research enquiry, it is worth reiterating the research questions. The practical research elements of this project set out to answer two main questions -

- Are young people attending Sunday worship joining in with the singing?

- Does the repertoire used in schools collective worship adequately prepare young people to participate in the sung worship of their church?

Are young people attending Sunday worship joining in with the singing?

The results of the ten church observations clearly show that the large majority of young people attending Sunday worship did not participate in the congregational song of their assembly on the day they were observed. The research team is satisfied that the level of sung participation of the young people observed was typical 1.

When the results were examined for the songs sung whilst the majority of the young people were present, the data showed an average of 34.7% of the young people present sang any one song. When this average was taken from the figures for every song in the service, regardless of whether or not most of the young people were in Sunday school, the average figure for the young people's participation was 34.3%.

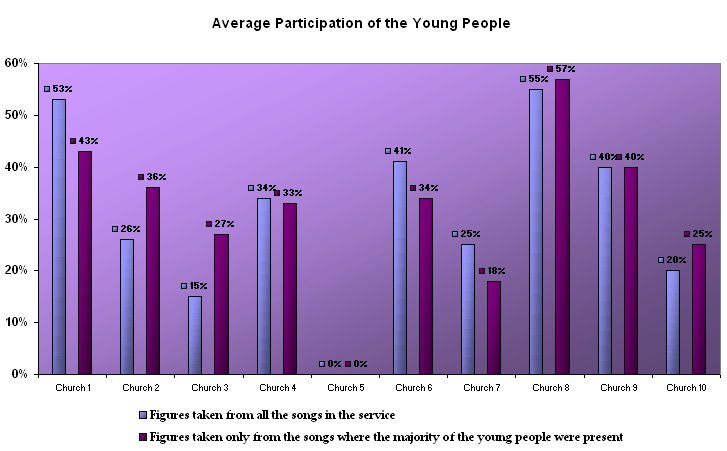

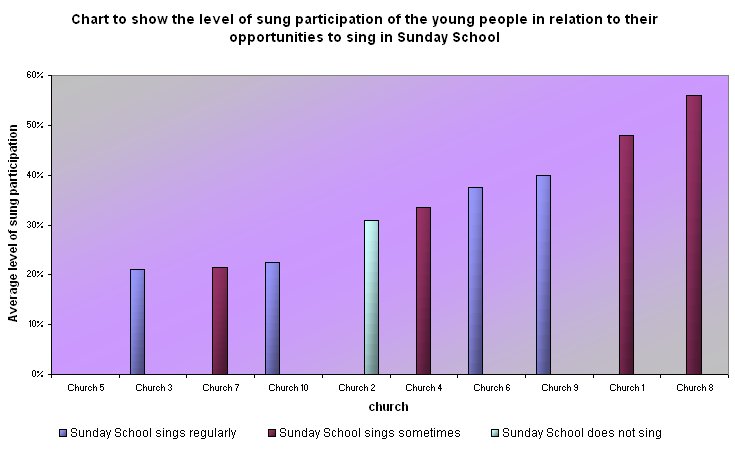

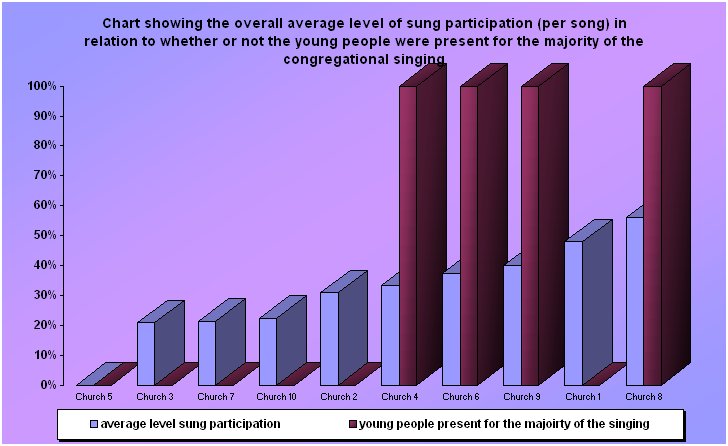

Looking at the data in these two ways had a variable effect. In some churches the average level of participation was shown to be higher when the majority of young people were present than when the figures were taken across the whole service; in other churches, looking at the whole service raised the average level of participation. This is shown in Figure 1 (below).

Figure 1

As the two averages for the whole sample were so close (34.7% when the majority of young people were present, and 34.3% across all the songs sung) it seemed fair to take the average of these two figures to give an overall average level of young people's sung participation - 34.5% 2.

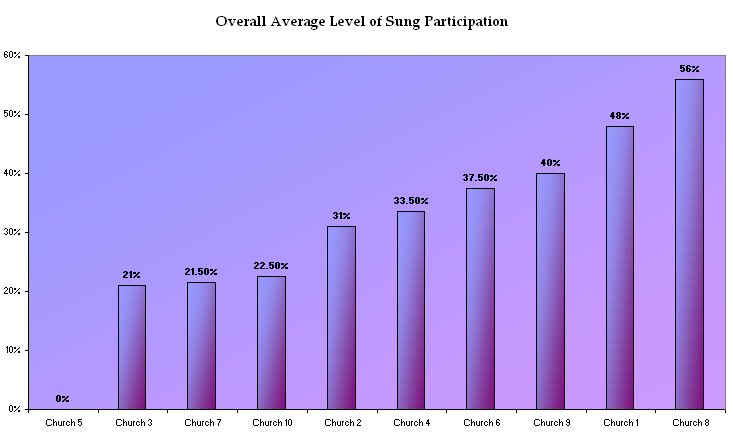

To offer the fairest picture of the level of sung participation of the young people in each church, the following chart (Figure 2) shows the average of these two sets of figures 3.

Figure 2

Interestingly, though these figures show considerable variation from church to church, no obvious denominational trend has emerged 4, indeed the churches with the lowest and highest levels of sung participation are both Anglican. The overall level of sung participation ranged from 21% at Church Three to 56% at Church Eight (discounting Church Five, where there were no children present to observe). However, only a study on a much larger scale will yield sufficient data to show whether or not the low level of participation in sung worship found in the area studied here is representative of the rest of the churches in the England.

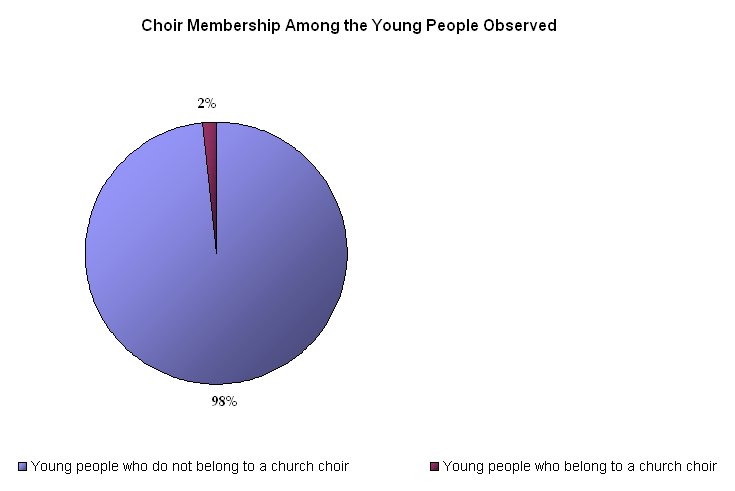

Young people as church choir members.

Church choir membership amongst the young people observed was extremely low at 2% 5, the incidence of which was not high enough to have any material effect on the overall level of sung participation at any of the churches concerned. The modern trend for running Sunday School concurrently with the main Sunday service means that in churches where there is a choir, the young people have to choose between choir membership and Sunday School 6. Some churches do not encourage young people to join the choir as they feel that the spiritual needs of children are more likely to be met in Sunday School.

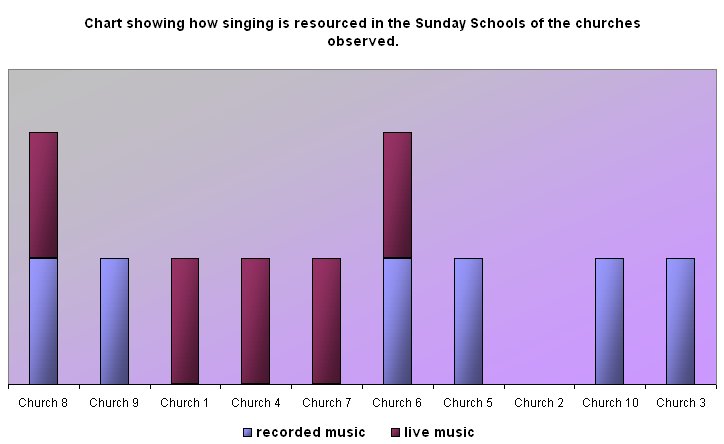

Figure 3

This pattern cannot be true of every church in the country, as the RSCM's annual round of choral singing courses continue to attract young singers and the cathedral schools remain popular and continue to flourish, but the results of this study suggest that the young people who are following that particular path of choral study and enjoyment are very much in the minority, largely confined to pockets of excellence that are by no means representative of the wider picture.

The young people miss out on most of the singing

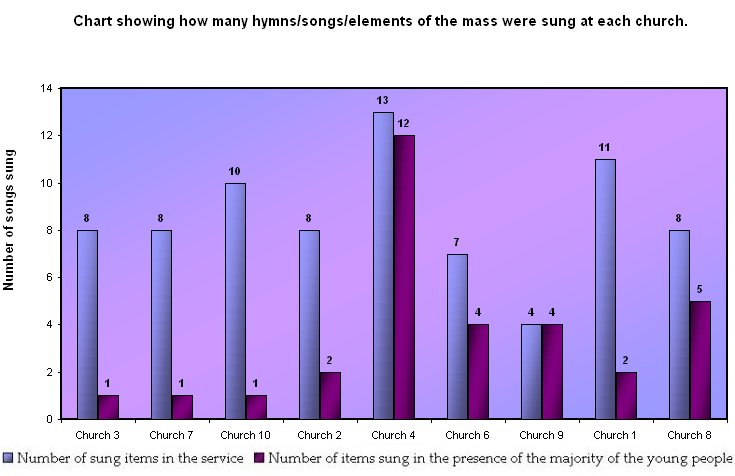

One glaringly obvious finding of the church observations is that the majority of young people miss out on most of the singing that happens in church because they are in Sunday School.

Figure 4

Figure 4 (above) shows that at five out of the nine churches where there were young people present, the majority of the young people missed out on the majority of the singing in church because they were in Sunday School 7. Two of the ten churches observed presented abnormal circumstances on the day they were observed - Church Nine was celebrating Harvest Festival, and Church Five had no Sunday School that morning and no children came to church. In both those churches, on a normal Sunday, the young people would be in Sunday School for the majority of the service. Therefore, in seventy percent (seven) of the churches observed, the young people are absent for the majority of the singing that takes place in church in the course of normal Sunday worship. In those seven churches, the young people have the opportunity to sing two songs or less with the main congregation. Taking an average across the eight churches where the circumstances were normal, an average of nine congregational songs are sung per service, but the majority of the young people are present for an average of three songs per service, meaning that they miss out on two thirds of the singing. This routine absence from the liturgy has to have a bearing on the level of sung participation amongst the young people attending church and has serious implications which will be discussed at length in Chapter 8. The three churches that constitute the thirty percent of the sample that keeps the young people in church for the majority of the singing were Church Eight, Church Six and Church Four. It is fitting that Church Eight, the only church observed that actively attempts to include young people in the main body of the service, had the highest level of sung participation of all the churches observed.

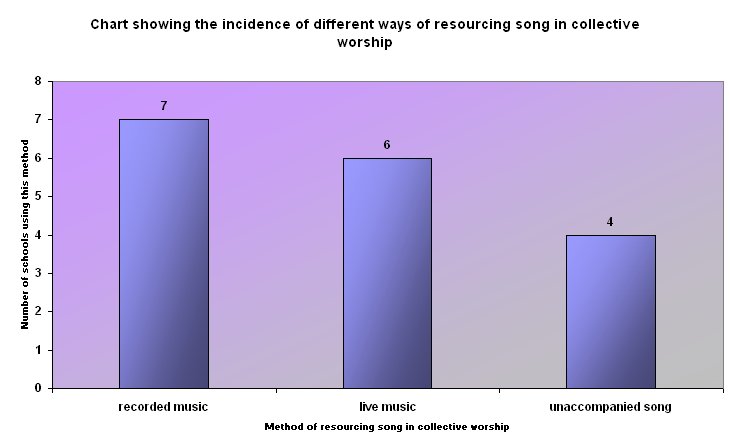

Singing in Sunday Schools

Ninety percent of the Sunday Schools of the churches observed sing together, though less than half of these sing regularly. There was no correlation between the regularity or otherwise of singing opportunities in Sunday Schools and the level of sung participation of the young people in church.

Figure 5

One would perhaps expect that the children who are accustomed to singing in Sunday School might participate more readily in the sung worship of their congregation 8. In reality, Sunday School singing does little to support the song of the assembly in the majority of the churches studied, as the repertoire sung in Sunday Schools rarely includes songs sung by the adult congregation. Moreover, and more importantly, the idiom of much of the music employed in today's Sunday Schools is so far removed from that of the repertoire favoured by the adult congregation that young people find it increasingly difficult to identify with and participate in the music of the normal Sunday worship (for a case study see Church Three Observation Report, App.p74-79).

Though I did not obtain a complete written list of the entire body of song of the Sunday School at any other church, conversations with clergy and Sunday School leaders have verified that the list of songs sung by the Sunday School group catering for 3-9 year olds at Church Three, is fairly typical of the musical fare found in Sunday Schools across the sample 9. All the Sunday Schools that sing are using Lighthouse songs, largely because the children know and enjoy them. One church - Church Ten, has made use of its school link, and is using the songs from one of the sources favoured at School Three in their Sunday School. The songs in question are from Sing Out 1, by James Wright (published by Gottalife Productions) 10. As is the case with most popular children's ministry material, the idiom in which these songs are written renders them incongruous in the context of normal Sunday worship.

Young people are unfamiliar with the sung repertoire of normal Sunday worship.

The research team conducted interviews with 130 out of the total 196 young people attending the services observed - 66%. A small number of those interviews were with young children (aged 3 to 6-years-old) and the particular difficulties in interviewing children of this age may have affected the data collected. These difficulties include:

'a tendency for the child to agree with the interviewer or to feel compelled to provide an answer even to 'nonsense' questions…there is clear evidence that children will respond to questions even if they do not know what they mean' (Dockrell et. al. 2000 p55).

Such problems are unavoidable, but in the light of this information the data has been vigilantly analysed and any answers that are clearly inappropriate 11 have been discounted from the statistics presented here.

The results of the interviews showed that 42% of the young people said they did not know any of the songs sung at the service observed. Only 32% said they knew more than one of the songs sung that day. This basic lack of familiarity with the songs of the assembly has to be a large contributory factor to the general low level of sung participation.

In many churches, the young people have insufficient exposure to the song of the assembly during normal Sunday worship for them to learn any of the hymns. With the Sunday Schools singing an almost entirely different body of song to that employed in the main Sunday service, the majority of the churches studied are doing very little to actively support their young people in participating in the song of the assembly.

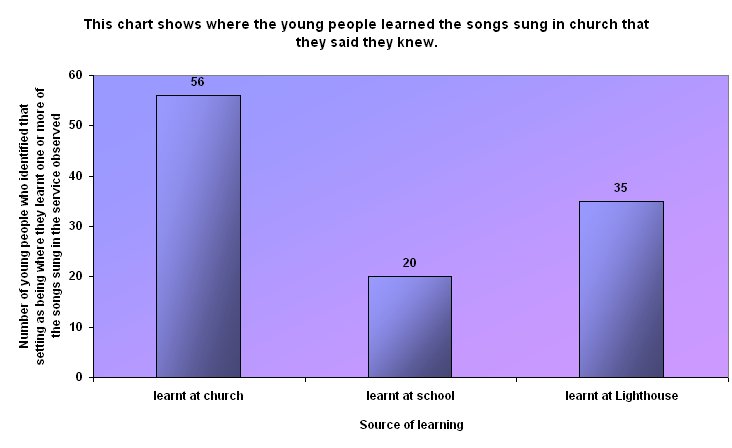

Where did the young people learn the songs they said they knew?

Figure 6 (below) shows where the young people learned the songs they said they knew 12. Church was most frequently cited as being the place where young people had learned the songs that were sung in the service observed. These findings substantiate the initial hypothesis that the repertoire of normal Sunday worship is particular each to church and that exposure to that repertoire in the church setting is the most effective means by which young people effectively learn that repertoire. The chart clearly shows that schools play the smallest part in teaching young people the songs sung in normal Sunday worship. Many more children said they had learned songs that were sung in church at Lighthouse, but this is perhaps misleading, as churches occasionally include Lighthouse songs in an attempt to include their young people, rather than because the Lighthouse songs are genuinely part of the repertoire suited to their normal Sunday worship.

Figure 6

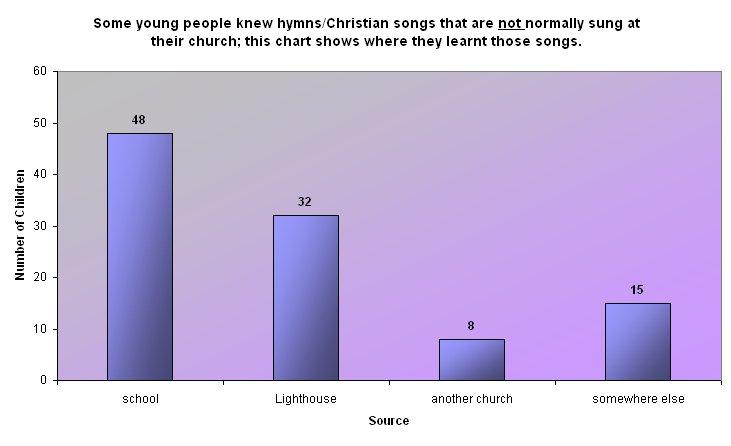

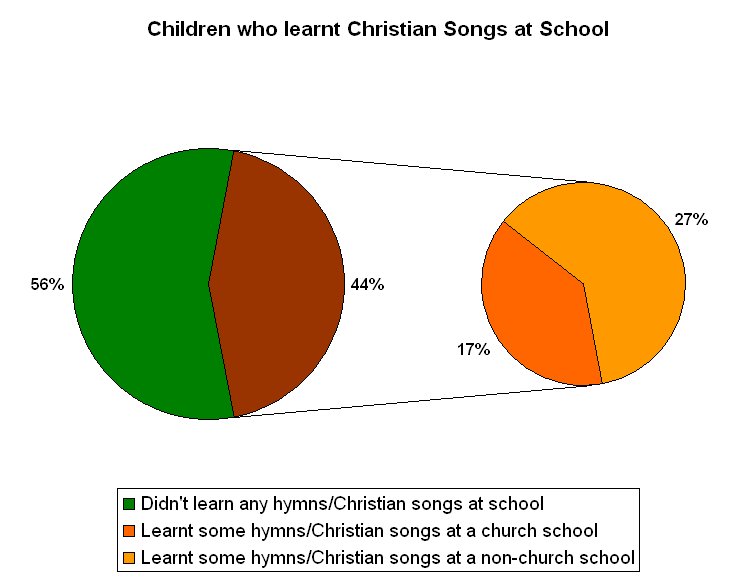

When the children were asked if they knew any hymns/Christian songs that were not normally sung at their church, a different trend emerged. Figure 7 shows that young people are indeed learning hymns/Christian songs at school. Figure 6 (above) and Figure 7 (below) serve to underline the fact that the repertoire learned in schools has little overlap with the repertoire used in normal Sunday worship; what is learned at church is sung in church, what is learned at school is sung in school. The problem is not that young people do not learn to sing in school nowadays, but rather that what they do learn to sing is of little help to them in church.

Figure 7

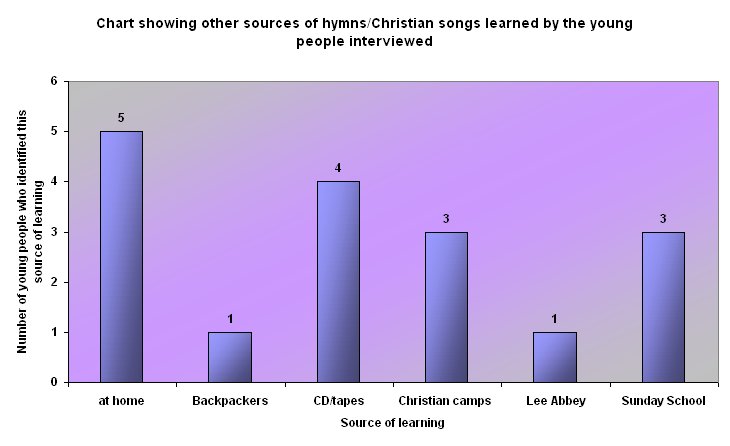

The 'somewhere else' category comprised of the following:

Figure 8

The following chart (Figure 9) was produced using the all the combined data about where young people had learnt the hymns/Christian songs they said they knew. Only 44% of the young people interviewed said they had learned any hymns/Christian songs at school. 17% of the young people interviewed said they had learned some hymns/Christian songs at school and attended (or had attended in the past) a church school (though 31% of the sample attended or had previously attended a church school). This reflects the growing trend among church schools and community schools alike to use songs in assembly that, whilst being congruent with Christian values, are not overtly Christian in their content. It also suggests that, contrary to popular belief, many of the non-church schools continue to use effectively use hymns/Christian songs in collective worship.

Figure 9

These figures may not give an entirely accurate picture of the Christian (or otherwise) content of the repertoire that is learned in schools. It is hard to believe that 56% of the children interviewed have not learned any Christian songs at school, as all the schools who responded to the questionnaire said they were using hymns/Christian songs of one sort or another in collective worship 13, but the figure is true to the answers given by the young people interviewed. I suspect many of the children who answered that they did not know any hymns/Christian songs that were learned in school either simply couldn't remember any 14, or maybe did not recognise the songs that they sing in collective worship as being hymns or songs of a Christian nature because many of them are nothing like the songs that are sung in church. Unlike the songs learned at events like Lighthouse, where the atmosphere is overtly Christian and therefore the children rightly associate the songs they sing there with Christianity despite the differences between the repertoire sung there and that which is sung in normal Sunday worship, it is possible that in schools, where in today's pluralistic society overt references to Christianity are increasingly avoided, children do not necessarily make the link between what they are singing in school and the faith that is fostered in church.

So what is being sung in schools?

'Well, of course, they don't sing in schools any more…'

This (or something similar) has been the typical response that has greeted my initial explanations when asked about my research. It is, however, an incorrect assumption. All the schools studied here are offering their children regular opportunities to sing in collective worship 15, and some offer additional singing opportunities for those that wish to join the school choir 16. In addition to this, all the schools have a weekly hymn practice 17.

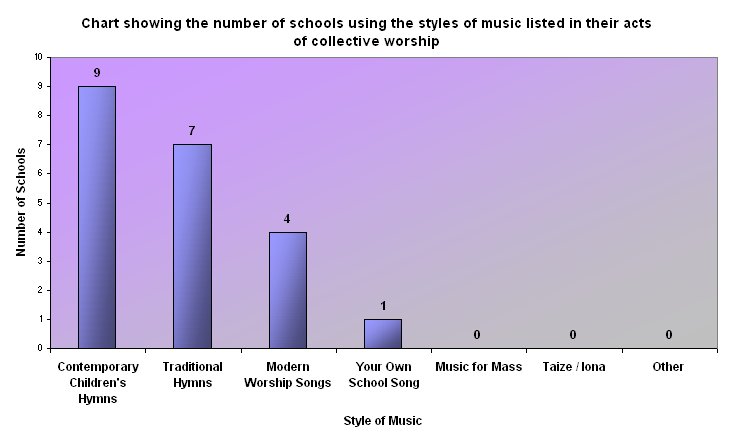

The questionnaire sent to the schools asked about what style of music was employed in collective worship; the responses are shown in the chart below. All the schools sing contemporary children's hymns. In addition to this, three quarters also sing traditional hymns, and half sing modern worship songs. Only one school has their own school song. None of the schools use the material published by the Iona Community or the brothers at Taize, and none sing any kind of mass setting.

Figure 10

Looking at Figure 10 (above) one could be forgiven for assuming that traditional hymns still have a firm footing in most schools and that many children are experiencing some the hymns favoured by their church 18 in the school setting. A closer look at the sources from which the schools take their repertoire, however, reveals something quite different.

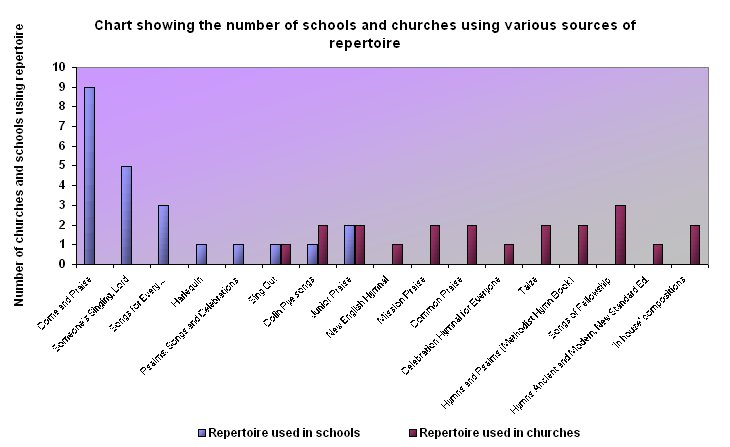

Figure 11

Figure 11 shows that there is actually very little cross-over between the sources of repertoire used in schools and the sources of repertoire used in churches for normal Sunday worship. The hymns contained in many of the volumes used in churches are not mutually exclusive; a goodly number of 'old favourites' are common to Celebration Hymnal for Everyone (Geary (ed.) 1994), Common Praise (Chadwick & Dakers (eds.) 2000), Hymns Ancient and Modern (1983), Junior Praise (Burt, Horrobin & Leavers (eds.)1997), Methodist Hymns and Psalms (1983), Mission Praise (Fudge, Horrobin & Leavers (compilers) 1983) and New English Hymnal (The English Hymnal Company Ltd. (compiler) 1986). Whilst there will therefore be considerable cross-over in the repertoire employed in the churches, the more modern publications used in schools harbour little such duplication. Two of the three sources of repertoire common to both churches and schools - Sing Out (Wright) and various songs by Colin Pye (Pye 2001 & 2004) - are single composer volumes comprised almost entirely of contemporary children's songs, and only one church uses songs from these in normal Sunday worship. The third, Junior Praise, has a strong bias towards contemporary children's songs, with a fair smattering of traditional hymns also included (though the texts of many of these have been butchered in the attempt to make them 'child friendly') 19, but in any case is still only used in two churches and two schools, none of which are linked.

Come and Praise (Marshall -Taylor (compiler) & Coombes (arranger) 1990) is by far the most popular source of repertoire among schools and is in use in all the respondent schools. The only two sources of repertoire used in schools containing repertoire similar to that which is in general use in normal Sunday worship are Come and Praise and Junior Praise. From the chart above, it is possible to see that, as only two schools use Junior Praise, over three quarters of the respondent schools rely on Come and Praise to provide any hymns that are likely to be sung in normal Sunday worship. Of the 149 songs in Come and Praise, only twenty-nine (19%) could be described as traditional hymns (either metrical hymns, or more modern hymns that have been admitted to the pages of hymn collections containing largely metrical hymns) 20. It is very unlikely that any of the schools (or churches for that matter) sing all twenty-nine of these 'hymns-in-common', further narrowing the repertoire learned in schools that aids children's participation in sung worship in church. The remaining 81% of the contents of Come and Praise is of the contemporary children's hymn variety that is not used in the normal Sunday worship of any of the churches studied.

It has to be understood that the children's contemporary hymn or school hymn - the kind found both in Come and Praise and in more modern collections like the Songs for Every … series - is an idiom all of its own. It is the child of the 'popular hymn', forerunner of today's modern worship songs, which was appeared in the 1950s, and the work of the group of priests, chaplains, musicians and schoolmasters known as The 20th Century Church Light Music Group 21. Whilst popular in the 1960s and early 1970s, the work of the 20th Century Church Light Music Group has, with a very few exceptions, now fallen from church use. Only ever intended to be ephemeral, popular hymns in this genre no longer sit comfortably in the normal Sunday worship of any of the churches observed, regardless of the style of churchmanship. It is little wonder, then, that school hymns, which continue to be cast into this mould, no longer constitute a transferable pattern of worship between school and church.

It is sometimes voiced in more traditional Anglican circles the notion that churches who worship using modern music do not experience the same difficulties in involving their young people as those preferring a diet of traditional hymnody. This is not true; there are a myriad of different idioms within modern church music that are not necessarily apparent to the uninitiated 22. Familiarity with one particular brand of modern music - the contemporary children's hymn - does not equal familiarity with any other idiom (though the jump may be smaller from contemporary children's hymn to worship song than from contemporary children's hymn to metrical hymnody). It can therefore be said that the majority of the repertoire sung in collective worship in schools does not aid young people's participation in sung worship in the normal Sunday worship of their church, as the repertoire contains few songs that transfer from school to church, and the bulk of the repertoire is in a different musical language to that employed in any of the churches observed.

The influence of the performance culture

The influence of the performance culture on church music is widespread. Though young people are particularly hard hit, it is not just those under the age of eighteen who are affected by the performance culture. Adults, whether school teachers, church musicians, Sunday School leaders, clergy or laity, are also influenced by the performance culture to a greater or lesser degree. We now have a whole generation of younger priests and school teachers who do not remember the days when everybody sang, and have lived their whole lives in the context of the performance culture. It is not just today's children that are unused to community singing - this is increasingly true of the adults around them. The whole of British society is now burdened by the expectation of the 'perfect performance.' Consequently, more and more schools and churches are resorting to singing along to CDs, either the karaoke-style backing track type, or worse still, CDs essentially intended for listening that constitute a complete performance in themselves and actually require no input from the congregation at all. Sixty percent of the Sunday Schools in the churches observed and seventy-seven percent of the respondent schools use CDs in this way.

There are two main reasons why such practice has emerged. Firstly, finding young people reluctant/unable to participate in the standard repertoire of the church, Sunday School leaders tried to find something the children knew. This is partly how the Lighthouse songs (and therefore the accompanying CDs) have become so popular in churches and schools in this area. Secondly, there is a shortage of people sufficiently confident in their musical abilities to lead young people in singing. There are, in fact, plenty of people out there perfectly capable of enabling song, but the performance culture places great pressure on all musicians to deliver the perfect performance, so much so that all but the most talented (or the most confident - the two things do not necessarily go together!) are silenced in favour of a pre-recorded performance 23. Unable to replicate the sound of the ten-piece Lighthouse band, many schools and Sunday Schools have chosen to sing along to the CD instead. This practice is destructive of congregational song, and therefore destructive of worship, for no pre-packaged commercially produced recorded performance can substitute for the real, live worship of the people present in that time and space.

'The Musicians' Union has become increasingly aware of a growing trend in the use of recorded music to replace musicians and singers in live performance…The Union believes this devalues our culture, and…seeks to remind people of the irreplaceable power, value and uniqueness of live music. There are many detrimental effects of the tendency to replace live performances with recordings…it short-changes audiences [congregations]…it destroys the uniqueness of the live experience… Research has shown that young people are inspired to learn an instrument or sing by experiencing a live performance, and to take away this opportunity risks destroying the UK's long heritage of musical talent' (Musicians' Union 2005 p23). [my emphasis]

This quote from Musicians' Union was written in the context of concern about the use of recorded music in place of live in theatre productions and stage shows. It is, however, equally applicable to church music in times when the culture of live music in worship is systemically undermined. The use of CDs to accompany song in schools, Sunday schools or churches serves only to reinforce the performance culture, and to alienate young people further from the musical norms central to the worship of the adult assembly.

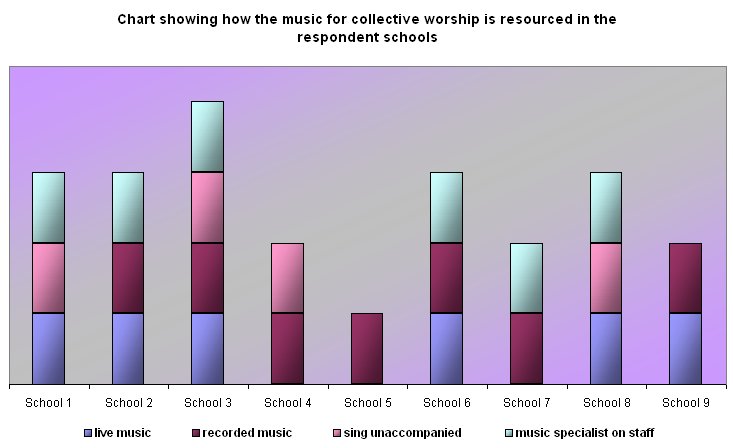

Live music versus recorded music in schools and churches

Thanks to the advent of pre-recorded backing CDs and the decline in the number of music specialists, some schools now use no live music at all in collective worship. Come and Praise, which when first published in 1978 demanded a live accompaniment, is now available with a backing CD, with the result that in some schools even the traditional hymns sung are not sung 'live' as they would be in church 24. There is a similar pattern in Sunday Schools, with many using recorded music (often because of a lack of musicians to facilitate the singing) - see Figure 13 (overleaf) 25. Some churches even use recorded music in worship for parts of the service 26. All the churches observed, however, used live music in normal Sunday worship, ranging from a solitary organist to five-piece band.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Recorded music can be useful when there is no music specialist available (and is infinitely cheaper than the costs of training a music teacher or church musician) but its use precludes the opportunities that otherwise arise for the encouragement and nurture of budding musicians 27. It also sets up the expectation of a perfect performance, which is not necessarily desirable or attainable in an act of worship. Far more important is that the worship offered to God is of the highest standard attainable by the people present, for the worship is theirs and nobody else's. If this means that people sing unaccompanied, then so be it. Richard Giles recommends that churches incorporate into their repertoire material,

'that can be sung without books - chants from Taize or Iona are good examples of this genre - which frees us up to sing more easily at those times when we need to be unencumbered by books (for example when we are on the move, or standing around the altar table), or when we together need to respond spontaneously to something which moves or challenges us within the liturgy (for example when the communion takes longer than expected or when prayer and the laying-on of hands is requested for a sick member). In making music we need to develop the capacity to travel light' (Giles 2004 p71).

The use of recorded music is the very opposite of 'travelling light'. It ties its users unbendingly to music of a predetermined mood, length, and instrumentation; all possibility of spontaneity is lost. It renders the worship of the people reliant on correctly functioning audio equipment and ultimately, the electricity supply 28. Singing either unaccompanied or to the accompaniment of live acoustic instruments is infinitely preferable.

Figure 14

Do church schools prepare their pupils more effectively for participation in sung worship than non-church schools?

The interviews are of little help in answering this question, as only a small proportion of the children interviewed attend church schools (31%). In any case it would be unwise to attempt to make a claim as to whether young people learn more hymns/Christian songs in church schools or community schools from data gathered in this way. The church observations do not answer this question either, as there is not a high enough concentration of children attending any one church who also attend the same school to effectively measure how experiences of song in collective worship affect young people's participation in sung worship.

What this study has shown is that church schools and community schools share a similar repertoire, and that both offer similar opportunities for their pupils to sing. From this one can deduce that the widely varying levels of sung participation found in the churches observed are more due to the differing sets of circumstances encountered in each church than to the young people's experiences of worship in school. The young people observed would appear to have had very similar experiences of singing in collective worship, regardless of the school attended; educationally, as far as sacred song is concerned, it is a level field when the young people arrive at the doors of church. It can therefore be said that it is young peoples' experiences of singing in church that most strongly affect the level of sung participation in normal Sunday worship.

Adults do not expect young people to integrate into the main Sunday Service

Alongside the formal research vehicles, the processes of setting up and carrying out the observations have yielded a large amount of rich qualitative data through the many conversations that have taken place with clergy and churchgoers during the course of the research. Though these have not been fully recorded, the salient points were noted and as these conversations have provided an extremely useful insight into the complexities of the issues surrounding the research.

In the course of these conversations I have been required to explain my theories countless times, and frequently had to defend my decision to observe regular Sunday worship (whatever that may be in any given church) instead of observing the family service. The earnest entreaties to 'come back and see a family service… we have much more for the children then'; the apologies that there weren't many children there or that we 'didn't see much' all served to underline precisely the point this study is making - namely that young people are not given the chance to successfully integrate into regular Sunday worship because adults do not expect such integration to happen and consequently fail to facilitate it. The prevailing attitude would appear to be that children/young people belong in Sunday School or the family service, and that regular Sunday worship holds little or nothing for them. It is these assumptions that have lead to the development of popular children's ministry that now pervades schools, Sunday Schools and Christian holiday clubs, offering models of worship that are so far removed from the culture of mainstream Sunday worship (with the possible exception of the more evangelical churches), that young people are unable to make the transition between one style and the other. These assumptions and the practices arising from them must be challenged and re-evaluated if young people are to be truly integrated into the worshipping life of the church.

Summary of findings

There was a low level of sung participation in all the churches observed 29 - an overall average of 34.5% - and only 2% of the young people observed were members of a church choir. On average, young people miss two-thirds of the singing that happens in church whilst attending Sunday school. 90% of the Sunday Schools in the sample studied sing, but the frequency of singing in Sunday Schools had no bearing on the level of sung participation observed. Sunday School singing does little to support young people's participation in sung worship due to the disparity of repertoire between Sunday School and normal Sunday worship. None of the statistics showed any denominational trend.

Many of the young people interviewed are unfamiliar with the repertoire of normal Sunday worship - 42% said they did not know any of the songs sung at the service observed. Whilst there is considerable potential cross-over in the repertoire used in the various churches observed, and a homogenous core repertoire used in schools (all use Come and Praise, though many supplement it with music from other sources) there is a very limited amount of material that is common to both schools and churches.

The idiom in which most of the school repertoire sits is not favoured in the worship of any of the churches observed. Furthermore, the increasingly common use of CD accompaniments in schools and Sunday Schools serves to further widen the cultural gap between the sung worship with which the young people are most familiar and that which they encounter in the course of normal Sunday worship.

The churches where the young people were present for the majority of the singing had higher average levels of participation than the churches where the children were absent for the majority of the singing. There was one exception, which proves the rule; Church One had an average of 48% sung participation, but their children were present for only two of the eleven songs sung. The church that had the highest level of sung participation was one of the few where the young people were present for the majority of the singing, and was the only church that made an active attempt to include young people in the main body of the service.

One can therefore conclude that if young people are to join in the singing that is an integral part of Sunday worship, the churches must take responsibility for creating circumstances in which their young people can learn to sing the songs of their congregation.

Figure 15

Back to Top |

Chapter 5

- 'When we collect data from children we can only ever measure their performance. We use performance as an indicator of a child's competence. For example, if we are interested in children's road crossing behaviour we might observe what they do on certain occasions. This is a measure of their performance. Their 'true ability' at road crossing behaviour is only inferred from their performance' (Dockrell, Lewis & Lindsay 2000 p53). In this way, the usual level of sung participation is taken to be inferred by the performance of the young people observed. Back to text

- Church Five was discounted from this calculation as there were no young people there to observe. The average figure of 34.5% was therefore obtained from the figures generated at the other nine churches observed. Back to text

- For instance, at Church One, the average level of young people's participation across the whole service is 53%, whereas the average level of young people's participation whilst the majority of the young people are present is only 43%. To find the fairest way of representing the level of sung participation of the young people in this church these two figures have been averaged thus: 53 + 43 = 96; 96/2= 48. Therefore the average level of young people's participation at Church One can be said to be 48%. Back to text

- A chart showing the denominational break-down of the sample can be found in the appendices, App.p39. Back to text

- 'There are 28,355 young people who are active members of a choir. The most popular age for choir membership is 10-13 years. Approximately one in three choir members is a young person (Statistics: Francis & Lankshear)' (Youth A Part 1996 p65). These statistics suggest a much higher incidence of choir membership among young people than was found in this study. It is possible that choir membership among young people has decreased in the ten years since Youth A Part was published (and that the data quoted could be more than ten years out of date, for no date was given for study from which the statistics quoted were taken). Back to text

- Out of the 196 young people observed, only two were singing in a choir. One was a Church Nine (where there was no Sunday School that morning because of Harvest Festival) and the other was at Cuhrch Four, where the Sunday School provision is only for 3-7 year olds - the choir member was a teenager. Back to text

- The 'number of items sung in the service' counts congregational items only. Items sung by choir alone have been discounted. Back to text

- It should be noted here that the Sunday School at Church Five also sings occasionally, but this did not show up on the chart as there was no average level of sung participation to plot as there were no children present to when the team observed. Back to text

- The 3-9 year olds' body of song can be found in the Church Three Observation Report, App.p75-76. Back to text

- A sampler CD containing excerpts from Sing Out and other Gottalife Productions songs can be found on the inside of the back cover of the appendices [apologies to those reading this online]. Back to text

- For example, when asked if there were any hymns/Christian songs that she would like to sing in church, a seven-year-old girl said she wanted to sings songs by the pop group, Abba (questionnaire number 007). One primary age boy (he declined to say how old he was, but the he did tell the interviewer which school he attended) responded 'Christmas carols' to the question, 'Which of the hymns/songs/ parts of the mass we sang in church today do you know?' This particular interview took place on 10th July, and no Christmas carols had been sung! (Questionnaire number 035). Back to text

- This was a 'tick all that apply' question, so the totals in the columns do not add up to the total of the young people who knew any songs in the service, as the some children have learned songs sung the service in more than one setting. Back to text

- Though many of the young people interviewed attend schools outside the sample area, the fact that 100% of the respondent schools use hymns/Christian songs in collective worship make it likely that all the other schools in the wider surrounding area are also doing so. Back to text

- In rather the same way as one's mind can go blank when asked to list what Christmas presents one received, some children may actually know many songs but be unable to name any. It is unlikely that this question is masking a large body of song unrecalled, however. Most people will say they got 'loads' of presents, even if they can't remember what they were. In the same way, a small number of young people responded similarly when questioned on their body of song, but many said they did not know any songs at all. Back to text

- The schools meet for collective worship on average five times per week and provide an opportunity to sing during collective worship on average four times a week. On average, the church schools offered the exactly the same number of opportunities to sing in collective worship as the community schools studied. Back to text

- Three out of the nine respondent schools have a school choir. All include both secular and Christian songs in their repertoire, and two out of the three choirs also sing songs from other faiths. All these schools have church links, and two out of the three are Church of England schools. Back to text

- One school sometimes has hymn practice twice a week. Back to text

- All the churches observed included traditional hymns in their services. 60% of the churches sang all or mostly traditional hymns. Even at each of the evangelical churches (Church Six, Church Seven and Church Eight) one traditional hymn was sung. Back to text

- For instance, Richard Hoyle's classic translation of Edmund Budry's text, 'Thine be the glory, risen, conquering Son, endless is the victory, thou o'er death hast won' (Thine be the Glory, number 120 in The English Hymnal Company Ltd. (compiler) (1986) The New English Hymnal. Norwich: Canterbury Press) has been reduced to 'Yours be the glory, risen, conquering Son, endless is the victory, over death You won.'(Yours be the glory, number 299 in Burt, P., Horrobin, P. & Leavers, G. (eds.) (1997) Junior Praise. London: Marshall Pickering). Back to text

- A complete list of the contents of Come and Praise, with the traditional hymns highlighted, can be found in the appendices, App.p134-139. Back to text

- See The 20th Century Church Light Music Group, App.140-141. Back to text

- At one church observed I had a conversation with one of the musicians who in the service that morning had shared a song he had written. I encouraged him to tell me some more about his work. He told me that he didn't usually write worship songs, and that his 'stuff was usually more prophetic'. As an Anglo-Catholic musician I hadn't thought about there being a distinction before, but there is as far as Independent Charismatic Evangelicals are concerned…I felt like my Grandma, who calls everything written after 1955 'pop music'! Back to text

- Two thirds of the schools with a music specialist on staff use recorded music in collective worship. Back to text

- For example, the children of School Nine only sing to live accompaniment once a week, when a peripatetic music teacher visits the school. The rest of the week the children sing to the Come and Praise CD. Back to text

- The Sunday Schools at Church One and Church Five also sing unaccompanied. It is possible that others also do so, but this was not information I originally intended to gather, so there are not figures across the sample to reflect this particular trend. Back to text

- See Church Eight Observation Report, App.p91-92. Back to text

- I began accompanying sung worship at the age of ten, when, during occasional absences of the deputy head (the only member of staff who could play the piano) I stepped in to play the hymns for assembly. At the time I could barely read music, so I played everything by ear. Limited to the keys of C, G and A minor, my playing wasn't great, but it was good enough and with this invaluable experience it quickly improved, leading me to where I am today. Back to text

- Technical failure can destroy worship. A malfunctioning CD player, feedback from the PA system, a digital organ that suddenly 'dies' - all these things have the potential to ruin the moment. Back to text

- ranging from 21%-56% Back to text

|

|