9

'Like a bridge over troubled water …' 1

Musical relationships between churches and schools

Schools are charged with a responsibility for handing on the Christian faith

Chapter 8 discussed how the integration of young people into normal Sunday worship is impeded by the lack basic lack of familiarity with the culture of church worship. If the culture of church worship as we know it today is to survive, it is vital that this culture be promoted and perpetuated in schools as well as churches, for through schools a great many more young people can be reached.

'The Church has a major problem in attracting young people to its services as a means of discharging its mission, and one that causes much concern. This bears directly on the future of the Church. In contrast, the Church has some 900,000 young people attending its schools' (Archbishops' Council 2001 p9).

Both the General Synod and the Archbishops' Council recognise that Church schools stand 'at the centre of the Church's mission to the nation' (Archbishops' Council 2001 pxi). It is not only church schools, however, that are charged with the task of handing on the Christian faith - all maintained schools are legally obliged to provide a daily act of worship that is 'wholly or mainly of a broadly Christian character' (Education Reform Act 1988).

The significance of collective worship

Collective worship is immensely important as a herald of the Christian faith. The rhythm and regularity of collective worship aids the 'inculcation of attitudes of mind' and it is the routine nature of collective worship that helps hymns and prayers to filter into the mind and memory over the years (Hall 2004 p1).

J.G. Williams writes:

'An act of worship communicates religious truths more powerfully than any direct kind of religious instruction - and it does so at a much deeper level because the truths are implicit rather than explicit, because in fact they are taken for granted' (Williams, quoted in RE Council for England and Wales 1996 p10).

In a society that is largely unchurched 2, religious education and collective worship bear the greatest burden in maintaining the cultural tradition of Christianity.

'…Religious education and collective worship have helped to keep in place some sort of religious culture, however tenuous this may be. That in itself is a valuable undertaking… the more so in that the evidence is beginning to suggest that the cultural threads are dangerously close to breaking' (Davie 1994 p135).

But the cultural threads between school and church, and therefore between church and wider society, are now threatened by the disparity between church worship and school worship, the result being that young people find it increasingly difficult to identify with and therefore participate in normal Sunday worship.

Collective worship and normal Sunday worship bear increasingly few similarities

One inescapable difference between church worship and school worship is the nature of the community involved. Church worship is corporate worship, in that it is shared and owned by all present. Collective worship differs in that it cannot be assumed to be the worship of a group of believers; it will be attended by those of other faiths and none, as well as both practising and nominal Christians. The worship offered by church communities and school communities will always bear this distinction. Patterns of worship that transfer between settings are therefore necessary to aid the integration of young people into the worship of the church, and of these, congregational song is of paramount import.

The hymn 'explosion' of recent years has enabled schools and churches to choose new music from an ever expanding selection of sources. As in virtually every other area of life, the children's market has been developed, with the result that schools and Sunday Schools are likely to adopt new music that is written specifically for children and is not particularly suitable for use in normal Sunday worship. This diversification has lead to a striking inconsistency between the body of song employed in churches and that which is common in school worship. The schools studied sing mainly contemporary children's hymns (from Come and Praise, Someone's Singing Lord, etc.). Some also sing modern worship songs (from the likes of Graham Kendrick) and songs from popular children's ministry writers such as Mark and Helen Johnson, Colin Pye, Alan Price, and James Wright. Though seventy-eight percent of the schools said they sing traditional hymns, in practice these are generally limited to the small selection available in Come and Praise 3. This study has shown that regardless of denomination or churchmanship, what is sung in normal Sunday worship rarely correlates with the repertoire employed in schools.

The importance of idiom

The problem of non-participation in sung worship is much deeper than young people's unfamiliarity with particular hymns. More important than the lack of common repertoire between churches and schools is the lack of common idiom, for the lack of familiarity with the musical language of the church alienates young people and impedes their participation in sung worship. The church has to recognise that,

'what has been intelligible since childhood for older singers is virtually a foreign language to those born after 1970 and that sociological fact should be appreciated before either group begins to condemn the sensibilities of the other' (Bell 2000 p151).

An email from a respected colleague 4 (written after her ten-year-old son had been to a praise party at our local theatre led by Dougie Dug Dug) - illustrates how the idiom in which music is written - and the style in which it is presented - affects young people's ability to participate.

'Interestingly, my 10yr old son who went to the Wycombe Swan kids morning said of the worship that he didn't know the songs but he could just sing along with it as if he knew the words and music and he did sing along which he doesn't always at church. So I guess it has to do with focus, atmosphere etc.' (Wallin, email 29/09/05) 5br>

The atmosphere at such events, made all the more potent by the sheer volume of the music, undoubtedly contributes to young people's ability to get caught up and carried along in the action; but this is not the only contributory factor. The Last Night of the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall is a spectacle of larger proportions than anything the Wycombe Swan can stage. When the audience sings along to Jerusalem 6, the volume, the energy, the sound of 5000- plus voices 7 quite literally surrounds one, the music sinking into one's very being. It is doubtful, however, that a ten-year-old child who had never before heard Jerusalem would find himself singing along as though he knew it, for Jerusalem is not written in the modern child's first musical language 8. Conversely, Duggie Dug Dug's music borrows heavily from mainstream popular music styles 9 and here lies the key to his success. His latest album is described thus:

'Okey Dokey! is the exciting new praise and worship album for kids from Duggie Dug Dug and it is out now! Lots of fun new songs in styles from Rap to Busted, McFly to Black Gospel! It seriously rocks! Lots of fun action songs too!' (www.duggiedugdug.co.uk accessed 11/12/05)

Young people growing up in a culture saturated with these (and other) popular music styles are naturally able to identify with the music of artists such as Dougie Dug Dug, and therefore are more likely to participate. It is ludicrous, however, to suggest that churches ditch the musical repertoire beloved of their congregation and attempt to become hip for the sake of their young people 10. The challenge to both churches and schools therefore has to be to find ways to introduce the idioms of church music into the consciousness of their young people, thus enabling them to recognise and be drawn into the music that is most often used in the worship of their church community.

The case for actively re-introducing school children to the music of the church

To aid young people's participation in normal Sunday worship it is necessary to actively re-introduce into schools music that is congruent with the styles favoured in normal Sunday worship. Purposefully introducing young people to the sound world of the various styles of church worship (and giving them a chance to actively participate in the same) can go some way to repairing the damage that has been done by the almost total divorce of repertoire common to school and church. Anglican Churches linked to a Church of England school have particular responsibility in this matter:

'The incumbent will encourage the school to see that the children become familiar with the main liturgy 11 and reciprocally see that the ministry to the school is on the agenda for meetings of the Parochial Church Council' (Archbishops' Council 2001 p54).

Anglican schools are charged similarly thus:

'For its part the church school should be continually asking itself how it can support the life of the Church community. It will want to provide an education in which children see the church as a familiar and friendly place…' (Archbishops' Council 2001 p54).

Community schools also have a responsibility to introduce their children to music of normal Sunday worship:

'Proper regard should continue to be paid to the nation's Christian heritage and traditions in the context of both the religious education and collective worship provided in schools. The Education Reform Act 1988 offers a framework in relation to collective worship which reflects primarily that tradition, while offering opportunities for the worship of other faiths in a context of mutual understanding and respect' (DfE July 1992 8.2). [My italics]

Whilst most of the material sung in the schools studied fulfils the requirement that it be 'wholly or mainly of a broadly Christian character' (Education Reform Act 1988), there is very little that reflects the great heritage of sacred song that until recent years was so very much a part of this nation and still forms the basis of normal Sunday worship in many churches today. Yet OFSTED offers the following guidance in their Guidance on the Inspections of Nursery and Primary Schools: 'Cultural development is concerned with both participation in and appreciation of cultural traditions' (HMSO 1995). On this point, David Lankshear comments that,

'One of the contributors to the culture of every area of the country will be the Christian church not least through the music, art, literature it uses in its places of worship and its services' (Lankshear 2002 p29).

Here, then, are the 'official' grounds on which community schools may be counselled to review their choice of songs used in collective worship. There is a yet heavier weight of expectation resting upon Anglican Church schools, where, in the light of current practice, changes to the sung repertoire could be said to be even more necessary.

'It is worth stating as a point that the law on daily worship that applies to schools without a religious character, that it should be 'wholly or mainly of a broadly Christian character' taken over the term as a whole, does not apply to Anglican schools, in which the law expects the daily worship to reflect Anglican beliefs and traditions of worship' (Lankshear & Hall 2003 p99). [My italics]

The musical diet offered in the church schools studied 12 (and, it is reasonable to suspect, in most Anglican schools in the country) falls a long way short of truly reflecting Anglican traditions of worship. Anglicanism today encompasses an astonishing breadth of churchmanship, from evangelical to Anglo-Catholic, with a similarly broad range of musical expressions to match. Church of England schools should therefore be teaching their children a similarly broad range of hymns/Christian songs. Greater attention must be paid to the inclusion of traditional hymnody, as well as to the music of Taize and the Iona Community, which has proved to be valuable in Anglican worship.

'The hope is therefore expressed…that the children might learn music which breeds in them a 'liking for' the Church's worship. As well as hymns, they should be taught canticles, psalms, responses and amens…' (Archbishops' Commission on Church Music 1992 p21).

Rebuilding a repertoire common to church and school through church-school links

Some churches, as previously discussed, are attempting to include young people in church worship by singing 'something the children know'. This is a reactive response that relies heavily on external agents (principally schools and Christian youth work initiatives) to provide the musical education of the church's young people. This approach would be workable if schools (or indeed, Sunday Schools) were teaching their children songs that aided integration into the worship of the church. In the light of this study, however, it is a response that, though well-intentioned, does nothing to foster young people's knowledge of the music of the church. Churches need to be proactive, both in educating their young people in the culture of church worship, and in reaching out to schools so that the children in the wider community might benefit similarly.

Rebuilding the repertoire common to church and school is of major importance in aiding young people's participation in the worship of the church. Five of the nine respondent schools said they welcome/would welcome input from an attached church in choosing appropriate music for collective worship. Interestingly, not all the church schools said they would welcome such input, but several community schools said that they would. Perhaps in some cases all that would be needed would be for the priest to suggest that certain hymns were learnt in addition to the repertoire already employed. In many schools, however, the lack of a musician on the staff 13 means that the entire school is limited to singing either unaccompanied or with backing tracks, as is the case in a third of the schools studied. In these instances a more creative approach is necessary; the sharing of resources, human and otherwise, between churches and schools can enhance the worshipping life of both 14.

Church-school links are limited in effectiveness by geographically fragmented patterns of church attendance.

When I designed this research project, I predicted that a repertoire common to churches and schools could be rebuilt by churches sharing their 'treasury of song' through improved church-school links; that schools would sing some songs that their linked church sing, thus providing the children of that church with a common repertoire on which to draw. The naivety of that prediction (and indeed, of Lankshear's recommendation that church-school links are most effective 'where both places have one of their sources of hymns in common' (Lankshear 2002 p59)) became apparent early into the fieldwork. When the responses of the young people interviewed were analysed it became apparent that church-school links have limited application in passing on a specific body of song due to the geographically fragmented patterns of attendance in each setting. The fragmentation of society is a well-documented general feature of modern life and this fragmentation is mirrored in patterns of church attendance. People do not necessarily attend their nearest church, or even the nearest church of their preferred denomination, further reducing the likelihood that children attending a particular church will attend (or have previously attended in younger years) any given school.

The first church observed had sixteen children in the congregation at the service observed. Of those sixteen, fifteen 15 were receiving education in a total of ten different establishments (nursery schools, schools and FE Colleges). Only half of the sixteen children present currently attend either of the church's two linked schools (five at School Nine and three at School Six). Clearly Church One cannot establish and maintain links with all those different educational establishments with a view to sharing its treasury of song. Analysis across all the churches and schools in the sample showed a similar pattern.

Maps detailing the schools represented by the children interviewed at each church observed can be found on App.p178-186. The maps show that the young people in every congregation are receiving education in a wide variety of establishments, with no single school being responsible for the education of the majority of the young people in any one church. Therefore, if the minister goes to his/her linked school saying, 'please can you learn such and such a hymn', even if the school complies with the request, it will only impact on a small proportion of the young people in that church's congregation.

A further series of maps (see App.p187-196) shows the spread of churches attended by the children interviewed for each school. Again, a large number of churches are represented in many of the schools - and these are only the ones discovered through interviewing the children present at the services observed 16. For example - out of the nine churches observed where there were any children to interview, five of them had at least one child attending School Five. This is shown on the map on App.p191 in the appendices. As is the case at Church One and all its represented schools, it is not feasible or sensible for the School Five to attempt establish links with the nine churches known to be represented there (and there may be many more than nine churches represented by pupils across the whole school).

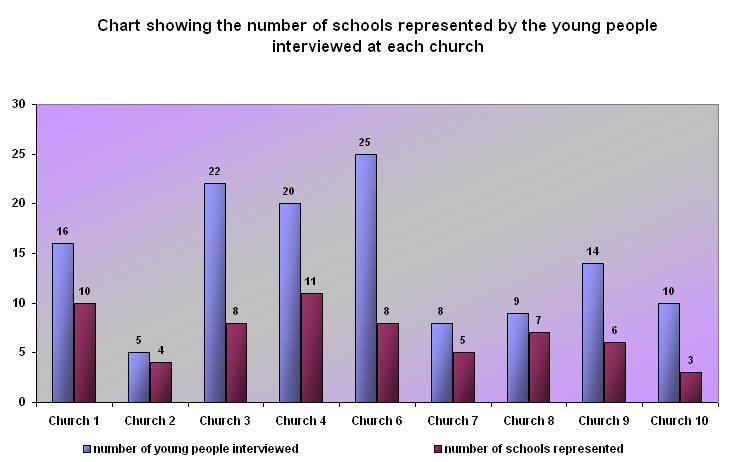

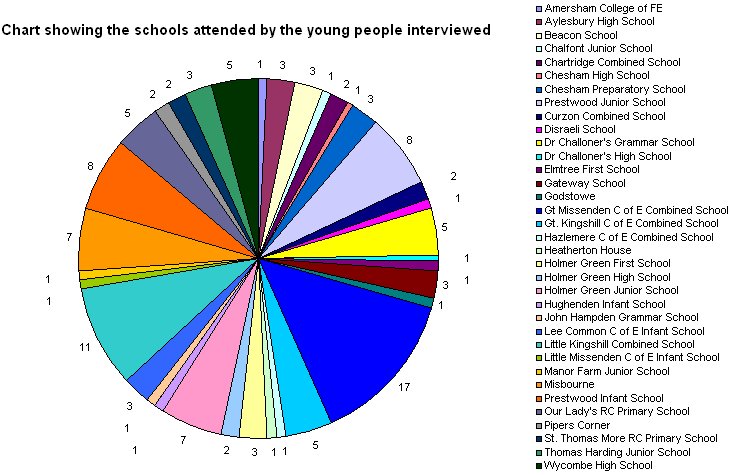

Each church observed had young people attending an average of seven different educational establishments (see Figure 16, below). Figure 17 (below) shows the extent of the fragmented pattern of school attendance across the whole church sample; of the 122 school-age young people interviewed, a total of 35 schools are represented.

Figure 16

Figure 17

There is no obvious place where a church-school link could be said to have sufficient children attending in both settings for there to be very much hope of songs learned in the school effectively transferring into church. Nowadays, churches are using such diverse repertoire that a standardised body of song learned in schools, no matter what the content, would song-for-song only be of limited use. This means that the problem of young people's unfamiliarity with the repertoire sung in churches cannot be solved merely by the vicar drawing up a list of the parish's favourite hymns and entreating the village school to learn them (though this, of course, will help). What can be achieved via this approach is the reintroduction of a repertoire representative of the idioms favoured in church worship, and this would be a valuable achievement indeed.

The cultivation of transferable patterns of worship through church-school links is an importunate necessity

Whilst it is always commendable to establish and nurture healthy church-school links, such links cannot be viewed as an effective route through which parishes can expect to reach more than a fraction of the young people attending their church. Despite their limited effectiveness in reaching these young people, church-school links are nonetheless invaluable in their potential both for reaching those 'unchurched' and in cultivating transferable patterns of worship between schools and churches.

'Cooperation between the churches and Church schools 17 in the selection of a proportion of the songs and hymns used in worship can greatly enhance the benefits that children gain in their musical education from the work of both school and church. It will also provide important links between the worship happening in each place' (Lankshear 2002 p59).

Church-school links that seek to share the music of each setting can be effective in counteracting the cultural alienation between church and the wider society, whereby familiarity with the idioms of church music and the promotion of the same can help to bridge the gulf between school and church worship.

Back to Top |

Chapter 10

- Simon, P. (1969) Bridge Over Troubled Water in Simon, P & Garfunkel, A. (undated) Simon and Garfunkel's Greatest Hits London: Music Sales, p40 Back to text

- 'It seems to me more accurate to describe late twentieth-century Britain - together with most of Western Europe - as unchurched rather than simply secular…' (Davie 1994 p12). Back to text

- A more detailed explanation of these finding can be found in Chapter 4. Back to text

- Philippa Wallin is Director of Music at Kings Church Prestwood, founder and director of the Churches Together Choir and the current Musical Director of Lighthouse Great Missenden. Back to text

- Wallin, P. (29th September 2005). Children's worship. Email to Chantler, E. Back to text

- Blake, W. (1757 -1827) & Parry, C.H.H. (1848 - 1918) 'Jerusalem', no 488 in The English Hymnal Company Ltd. (compiler) (1986) The New English Hymnal. Norwich: Canterbury Press Back to text

- The official seating capacity of the Royal Albert Hall is 5222 (www.royalalberthall.com/rah/mainsite/pdf/2062_education_fact_sheet.pdf accessed 14/12/05). Back to text

- 'Although music is a universal human culture, it is not a universal language, for its dialects are many, making communication unintelligible when communities do not know what one another's music means' (Winter 1984 p234). Back to text

- Sound clips from his more recent work can be heard at www.duggiedugdug.co.uk on the 'Dug's Studio' page. Back to text

- This would be the liturgical equivalent of taking one's elderly relatives to a trendy night club - it would be an uncomfortable and embarrassing experience for all concerned. Back to text

- Sacred song 'forms a necessary and integral part of the liturgy' (Sacrosanctum Concilium 112). Back to text

- All the church schools that agreed to take part in this study were Anglican. Back to text

- 'An additional cause for disquiet is the present shortage of music teachers in primary and secondary schools. This has now been officially recognised and it is expected that extra student places will be provided to make up the deficiency' (Archbishops' Commission on Church Music 1992 p206-207). Back to text

- See Post Script 1, p106-107. Back to text

- One of the children in attendance was only two years old and therefore not yet receiving formal education. Back to text

- It is likely that there are many more children attending a greater number of churches still as some may well attend churches that were not included in the sample. Back to text

- Or, indeed, between any school and a linked church. Back to text

|

|